With a growing number of cities across Canada looking to office conversions to remove older, lower class space from their inventories, developers are calling out the challenges of pursuing redevelopment.

The success of the Downtown Development Incentive Program that Calgary launched in 2021 has set the pace for other cities, garnering 28 proposals before being paused Oct. 17 pending new terms of reference and additional funding.

A total of $153 million has been allocated to the program, which offers an incentive of $75 per square foot to convert office space to residential, hotel, school and performing arts space. It aimed to remove 6 million square feet of vacant office space from the market by 2031.

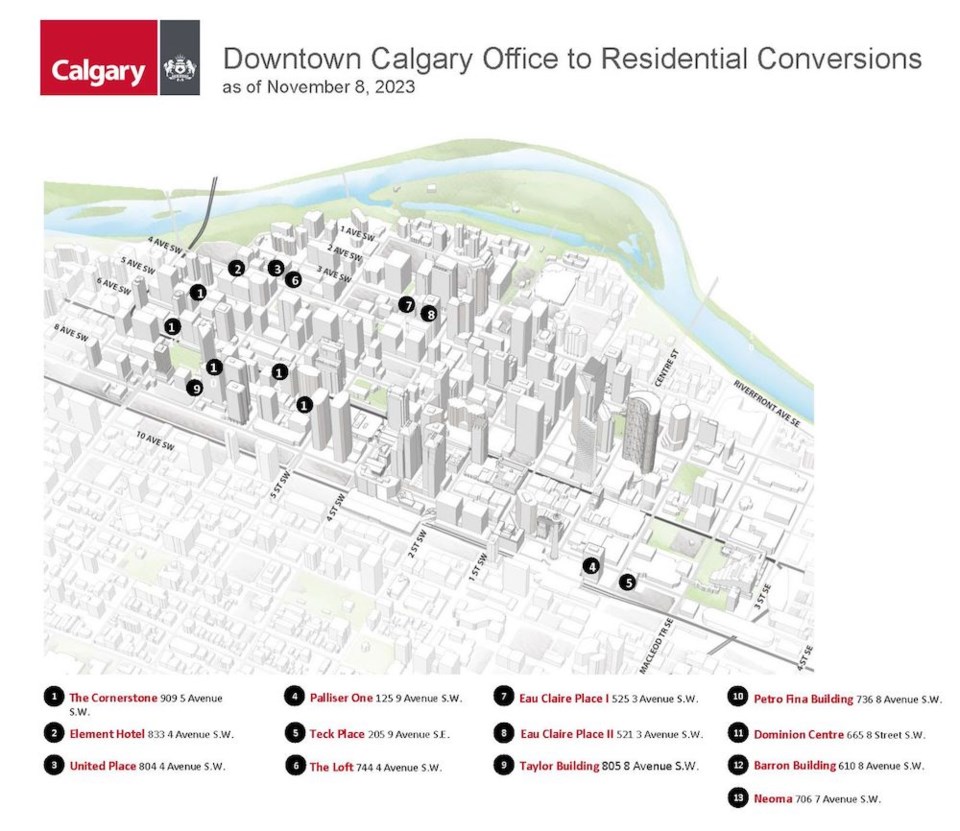

A total of 13 projects, expected to remove 2.3 million square feet of office space and create 2,300 new homes, were approved. Three of the projects have been completed and two are in progress.

But it’s the remaining eight that are have held back the program, and point to the challenges facing developers that initially sought city support for their projects.

“Physically, it’s very difficult to convert,” Greg Kwong, managing director with CBRE Ltd. in Calgary, told the Western Canada Lodging Conference in Vancouver on Nov. 2.

Office towers typically have a different shape than hotels or residential projects, making them challenging to reconfigure.

“The biggest issue is the perfect floor plate design for an office building is the centre core, with 45 to 50 feet expanse from the core to the window mullions, and a square,” Kwong explained. “A hotel, the perfect design is typically a rectangle, or an L-shape, where you’ve got an elevator and a long, narrow corridor with rooms on each side.”

Plumbing and other elements are also challenges, as most offices don’t have multiple showers, toilets or kitchens on each floor. Seismic and energy standards are also different.

“That’s why Calgary has not converted a lot of vacant buildings,” Kwong said.

The developers whose projects have been approved recognize the challenges, and given rising construction and financing costs, have held off despite the city’s $75 per square foot incentive.

The city, which wants to see buildings restored to their highest and best use – and in turn, contributing to the city’s welfare through property taxes – has paused the incentive program.

“They’re saying the money’s there, if you’re going to go ahead let’s go, but if you’re not tell us because we have to figure something else out,” Kwong said.

BILD Calgary, which represents the city’s residential development industry, did not provide comment.

The challenges facing developers in Calgary are even greater in Vancouver, where conversion projects are also being discussed despite one of the lowest downtown office vacancy rates in the country and a history of balancing the need to protect jobs space with a persistent housing shortage.

In 2004 the city placed a two-year moratorium on office conversions to protect downtown jobs space from rampant condo development. The wave of new towers built over the past decade is testimony to its foresight.

While Amacon is mulling the conversion of 1144 Burrard Street to a hotel, downtown office space hasn’t lost its lustre. Speakers at recent industry conferences say any changes of use in the city will have to be market-led.

“There’s got to be an incentive – not just a tax incentive. I think there has to be an impetus,” Christopher Mullins, senior director, cost and project management with Altus Group told a panel on office conversions at the Vancouver Real Estate Strategy and Leasing Conference on Nov. 7.

Calgary’s incentive of $75 a square foot falls short in the face of residential construction costs of $500 to $700 a square foot, meaning developers are more likely to find success – and civic approval -- with a mixed-use project.

“In general, mixed-use is more likely to work,” Mullins said. “Stress-test the options. … When you model it, especially when you do the feasibility, it’s surprising what works, what doesn’t.”

Avison Young principal Glenn Gardner was more emphatic when asked about the prospects for Vancouver office conversions at the Oct. 26 breakfast meeting of NAIOP Vancouver.

“There’s no chance,” he said. “Think about what it takes to build an office building in this city, let alone convert an existing office building to a residential building. I can’t see a scenario where it happens.”